Bone needles found at the 12,900-year-old site of La Prele in Wyoming, the United States, were produced from the bones of foxes; hares; and felids such as bobcats, mountain lions, lynx and possibly even the now-extinct American cheetah; these animal bones were used by the early Paleoindian foragers at La Prele because they were scaled correctly for bone needle production and readily available within the campsite, having remained affixed to pelts sewn into complex garments, according to new research from the University of Wyoming.

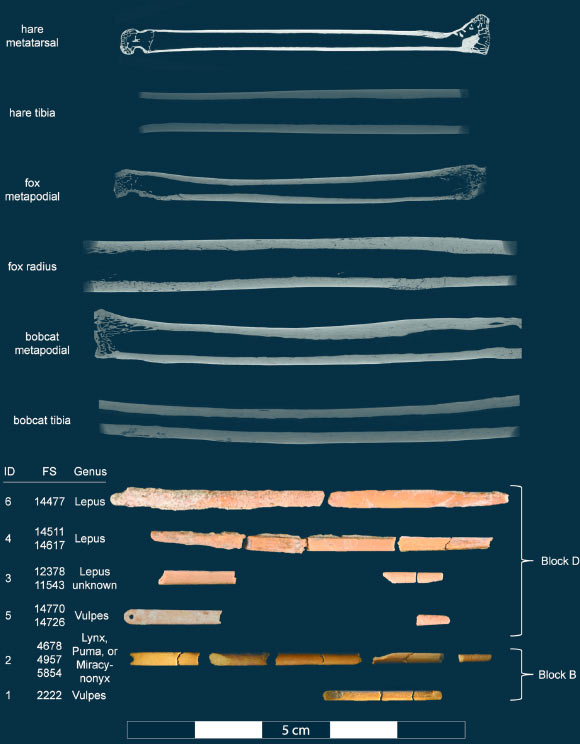

La Prele bone needle and needle preform reconstructions and Micro-CT scans of comparative faunal specimens. Image credit: Pelton et al., doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313610.

La Prele is an Early Paleoindian mammoth kill and campsite on a tributary on the North Platte River near Douglas, Wyoming.

Ten seasons of excavations in four major blocks have yielded tens of thousands of artifacts associated with a single occupation.

Among the wide diversity of artifacts recovered from the site thus far are 32 bone needle fragments.

“Our study is the first to identify the species and likely elements from which Paleoindians produced eyed bone needles,” said Wyoming State Archaeologist Spencer Pelton and colleagues.

“Our results are strong evidence for tailored garment production using bone needles and fur-bearing animal pelts.”

“These garments partially enabled modern human dispersal to northern latitudes and eventually enabled colonization of the Americas.”

In their study, Dr. Pelton and colleagues examined the bone needle fragments from the La Prele site.

They compared peptides — short chains of amino acids — from these artifacts with those of animals known to have existed during the Early Paleondian period, which refers to a prehistoric era in North America between 13,500 and 12,000 years ago.

The comparison concluded that bones from red foxes; bobcats, mountain lions, lynx or the American cheetah; and hares or rabbits were used to make needles at La Prele.

“Despite the importance of bone needles to explaining global modern human dispersal, archaeologists have never identified the materials used to produce them, thus limiting understanding of this important cultural innovation,” the researchers said.

Previous research has shown that, in order to cope with cold temperatures in northern latitudes, humans likely created tailored garments with closely stitched seams, providing a barrier against the elements.

While there’s little direct evidence of such garments, there is indirect evidence in the form of bone needles and the bones of fur-bearers whose pelts were used in the garments.

“Once equipped with such garments, modern humans had the capacity to expand their range to places from which they were previously excluded due to the threat of hypothermia or death from exposure,” the scientists said.

“How did the people at the La Prele site obtain the fur-bearing animals?

“It was likely through trapping — and not necessarily in pursuit of food.”

“Our results are a good reminder that foragers use animal products for a wide range of purposes other than subsistence, and that the mere presence of animal bones in an archaeological site need not be indicative of diet.”

“Combined with a review of comparable evidence from other North American Paleoindian sites, our results suggest that North American Early Paleoindians had direct access to fur-bearing predators, likely from trapping, and represent some of the most detailed evidence yet discovered for Paleoindian garments.”

The findings were published in the journal PLoS ONE.

_____

S.R. Pelton et al. 2024. Early Paleoindian use of canids, felids, and hares for bone needle production at the La Prele site, Wyoming, USA. PLoS ONE 19 (11): e0313610; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313610