The Neanderthal groups that inhabited a cave in what is now Spain approximately 46,000 years ago gathered and collected fossils, according to a paper published in the journal Quaternary.

Collecting is a form of leisure, and even a passion, consisting of collecting, preserving and displaying objects.

When we look for its origin in the literature, we are taken back to ‘the appearance of writing and the fixing of knowledge,’ specifically with the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE), and his fondness for collecting books, which in his case were in the form of clay tablets.

This is not, however, a true reflection, for we have evidence of much earlier collectors.

The curiosity and interest in keeping stones or fossils of different colors and shapes, as manuports, is as old as humans are.

For decades, archaeologists have had evidence of objects of no utilitarian value in Neanderthal homes.

Several European sites have shown that these Neanderthal groups treasured objects that attracted their attention.

On some occasions, these objects may have been modified to make a personal ornament and may even have been integrated into subsistence activities such as grinders or hammers.

Normally, one or two such specimens are found but, to date, no Neanderthal cave or camp has yielded as many as Prado Vargas Cave in Cornejo, Burgos, Spain.

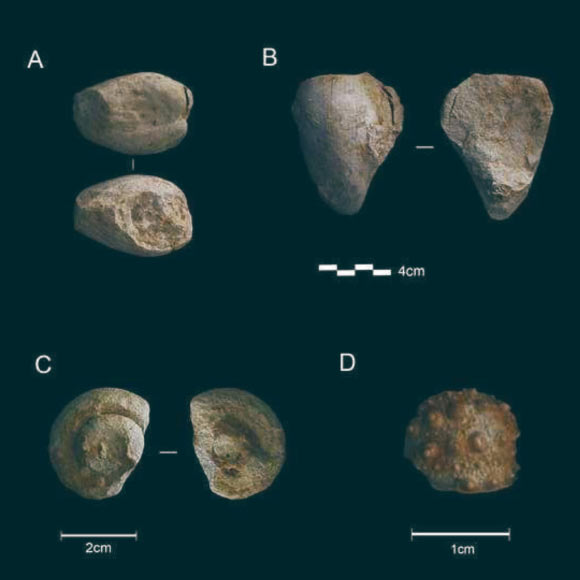

In the Mousterian level of the cave, Universidad de Burgos archaeologist Marta Navazo Ruiz and her colleagues found an assemblage of 15 marine fossils dating back to the Upper Cretaceous epoch.

“All specimens belong to the phylum Mollusca, except for one, belonging to the phylum containing the echinoderms (Echinodermata),” they explained.

“Among the mollusks, half belong to the class of bivalves (Bivalvia) and the other half to the gastropods (Gastropoda).”

“Within the gastropods, the family best represented, with six specimens, is Tylostomatidae. This fossil group belongs to the same class as modern snails and they could reach 10 cm; they have a holostomatous shell with several spirals, the last of which is larger.”

“The Tylostomatidae fossils found in the cave were snails that lived on shallow seabeds millions of years ago.”

The fossils, with one exception, show no evidence of having been used as tools.

Thus, their presence in the cave could be attributed to collecting activities.

“It seems clear that the selection and transport of these fossils by these Neanderthals into the cave held some meaning and symbolized something, which has led the research team to propose various hypotheses to explain this behavior,” the archaeologists said.

“They might have been collected simply for aesthetic reasons because the Neanderthals found their shapes attractive; for exchange within the group or with other Neanderthal groups; as toys; or to reinforce their cultural identity as an element of the group’s own social cohesion, in the sense that the fossils bound them directly with the territory they inhabited.”

“It is possible that the collecting was performed by the children of the group,” they noted.

“Studies with our own species have shown that the collection of objects is a characteristic of childhood.”

“According to specialists, collecting behavior appears in human children between the ages of 3 and 6, at the moment they begin to be aware of themselves, and it continues until they are 12 years old.”

“Collecting continues during puberty, though less intensively, while from the age of 18 this behavior peters out and does not emerge again until they are about 40.”

“It is possible that the Prado Vargas Neanderthals found the fossils either intentionally or by chance, but what is clear is that carrying them to the cave was deliberate, systematic and reiterated, and we can recognize their efforts and interest in collecting these fossils in this,” the researchers concluded.

“Thus, the Neanderthals of this cave in Burgos have become the earliest fossil collectors we know of today in our evolutionary process.”

_____

Marta Navazo Ruiz et al. 2024. Were Neanderthals the First Collectors? First Evidence Recovered in Level 4 of the Prado Vargas Cave, Cornejo, Burgos and Spain. Quaternary 7 (4): 49; doi: 10.3390/quat7040049